UF researchers use gene therapy to treat pulmonary dysfunction in Pompe disease

By Mindy Cameron

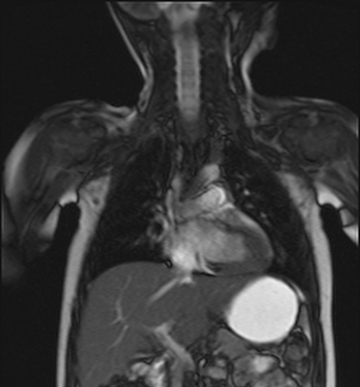

This MRI of a research participant was taken six months after receiving gene therapy to the diaphragm. Researchers measured the descent of the diaphragm during breathing as a way to evaluate muscle function and changes in breathing.

UF researchers have successfully used gene therapy to treat patients with infantile onset Pompe disease, a progressive condition that severely compromises cardiopulmonary function in the first years of life.

The team at UF’s Powell Center for Rare Disease Research and Therapy conducted the first in-human study of gene therapy to treat respiratory dysfunction in patients with infantile onset Pompe. In the study, which began in 2011, an adeno-associated virus vector was used to carry a functional copy of the affected gene to muscle cells in the diaphragms of nine patients.

In study results published online in Experimental Neurology, breathing function improved in patients after gene therapy, compared to a period of treatment with breathing exercises before the gene therapy. The improvements were greatest in patients who were not on full-time ventilator support at the start of the study, and these patients continued to breathe independently for long periods years after treatment.

“These findings are significant because Pompe disease, even when well-controlled, is progressive. Functional improvements in breathing are not the expected natural course of Pompe disease,” said Barbara Smith, Ph.D., P.T., a co-investigator of the study and a research assistant professor in the PHHP department of physical therapy.

Pompe disease is a genetic disorder caused by the absence or deficiency of alpha-glucosidase, an enzyme required to break down the complex carbohydrate glycogen and convert it into glucose. The infantile onset form of the disease is the most severe, with untreated patients experiencing significant heart and lung failure by the second year of life.

Gabi Hernandez’s child was 4 years old and in a steady state of cardiopulmonary decline when the gene therapy was administered. She said her child’s health improved within months after dosing, noting that her child had a stronger cough and discontinued use of mechanical cough assistance and inhalers. Hernandez said her child’s cardiopulmonary health remains stable two years after treatment.